In our latest Belgian exhibitions article Liz Newmark explores the European House of History’s fascinating look at life through posters.

Are posters – the world’s first mass medium – still relevant in today’s Internet/social-media obsessed age? What will happen to the poster in a world where most information is looked at on screen? Will these amazing influencers of yesteryear still be relevant in ten years’ time?

These are all questions addressed in the European House of History’s new free exhibition ‘When walls talk’, showing until 13 November 2022. In this whistle stop tour of history through this special art form, visitors are treated to some 150 posters from across Europe over the last 100 years. The posters are grouped into special sections. All titles and extra information – as befits such a European institution – are available in French, Dutch, English and German.

Visitors can explore how posters have influenced our ideas, views and perceptions of Europe. From the propaganda of the World Wars and the Cold War to the rise of cultural exchange, tourism and social justice movements after World War II, the exhibition reveals “complex layers of European division and unity,” lead curator Perikles Christodoulou told the 28 April press launch.

“Posters function as vehicles to inform, but also educate and even manipulate. They have dominated the public space, jostling for our attention and confronting us with the ideas of our time,” Christodoulou explains. “Whilst posters offer invaluable insights into European life and what it is to be European, they can also reveal darker stories of how society has been moulded by economic and political forces.”

For Christodoulou, posters are essential. Just like history, they illustrate the economic and social developments in education, travel and sport, political movements including Solidarność and Communism and major events like wars and terrorist tragedies that shape our world, making them the “chroniclers of their time par excellence”. They also – via commands, repetition and particularly humour – exploit the power of words and images to inform, influence and even manipulate their audiences.

The expertly-picked selection of posters from some 5,200 in the museum’s archives, look at ‘turmoil and unity’, ‘barriers and connections’, ‘activism and protest’; and then imagine if there is life, ‘after the poster’. There is also a special sit-down section where you can watch films about Europe inspiring iconic posters such as Europa by Lars Von Trier or Europe 51 by Roberto Rossellini.

You will see well-known classics like the propaganda posters of the First and Second World War such as ‘Britons (Lord Kitchener) wants you’ or the American version ‘I want YOU for US Army’. Both posters literally stare the viewer in the face. ‘Si’ showing Mussolini is also a stunning piece. His black shirt reveals thousands of photos of tiny black-and-white heads clearly at a rally. The Nazi period piece: ‘Auch du sollst beitreten zur Reichswehr (You must also enlist to the Reich’s Army)’ is chilling in its darkness.

There are fascinating comparisons to be made for example between the posters advertising the Olympic Games pre and post Second World War. The latter, with leaders calling for peace across borders, are far less bombastic and controlling.

The exhibition also highlights beautiful travel posters of the 1950s when there was hope perhaps that an East-West divide would be healed by a very efficient train service. Notably highlights are: ‘Trans Europ Express connects 70 European cities’ or even, 20 years later, the more muted ‘Nous construisons l’avenir’.

Immigration is another theme tackled excellently in the museum. Posters include the iconic 1992 Oliviero Toscani Benetton poster of migrants hanging from a ship. This provoked mass criticism that you should not use human tragedy to sell products; although another view is that people may be encouraged to act without relying on immigration policy. Myriad others including the stark and impressive May 1968 riot-inspired ‘Frontières = Repression” (Atelier populaire Paris, 1968).

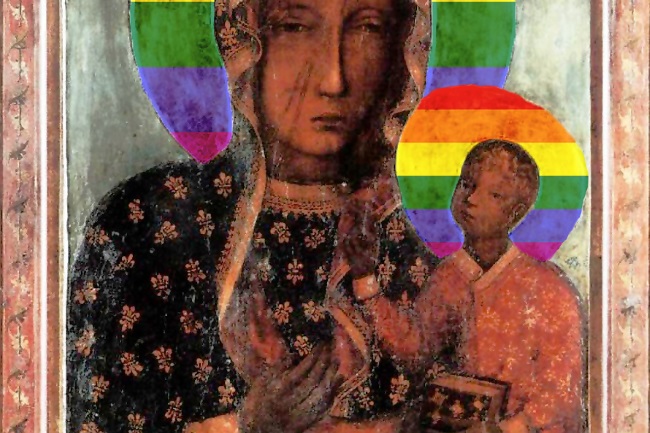

There are further chilling records of racism and homophobia. For Guido Gerrichhauzen, head of the museum’s learning and outreach department, who treated me to a fascinating guided tour, ‘Rainbow Madonna’ is a notable museum must-see. When it came out in 2019, the poster became a cause célébre. Its author Elżbieta Podleśna (1968) was even taken to court for daring to put pictures of black Madonnas in rainbow colours in her protest against the anti-gay Polish government.

The more modern posters give a stark reminder of the terrorist attacks and dictators ever present today. “I am Charlie” is almost poignant now, in the wake of the January 2016 killing; and Doğan Arslan warns ‘Voice of democracy in danger!’ in his blood-spattered depiction of Turkey/Slovakia tensions in 2018.

Last but not least, there is a show-stopping poster highlighting the war in Ukraine: “There is nothing scarier than unlimited power in the hands of a limited man,” we read, as a tiny Vladimir Putin peers out at us from a blue and yellow affiche.

Even with the digital advances of the 21st century, posters are still used to influence our behaviour and allegiances. Using every possible strategy to sell a message, including seduction, shock and statistics, the poster is definitely not dead.

The exhibition comes complete with a full learning programme of talks, guided tours and workshops for schools. There are special activities for the 19 May Nocturne evening opening and 10 September Park Leopold Day.

Ideally you will also have time to visit the permanent exhibition taking a transnational approach to the origins and evolutions of European history. Over five floors, and with so much to take in, why not take it slow? Gerrichhauzen asks, telling Together enthusiastically: “One visitor spent three days here, taking one day to do each floor.”

www.historia-europa.ep.eu/en/when-walls-talk